‘Nervous, self-doubting, fearlessly brave’

I discovered James Courage when I read Peter Wells and Rex Pilgrim’s Best Mates, a landmark book on New Zealand gay writers. Courage seemed like someone I’d want to know about: creative, eloquent, serious – and his writing had even been censored. A Way of Love, the first gay novel by a New Zealander, was banned in 1961 by a bossy group of government bureaucrats.

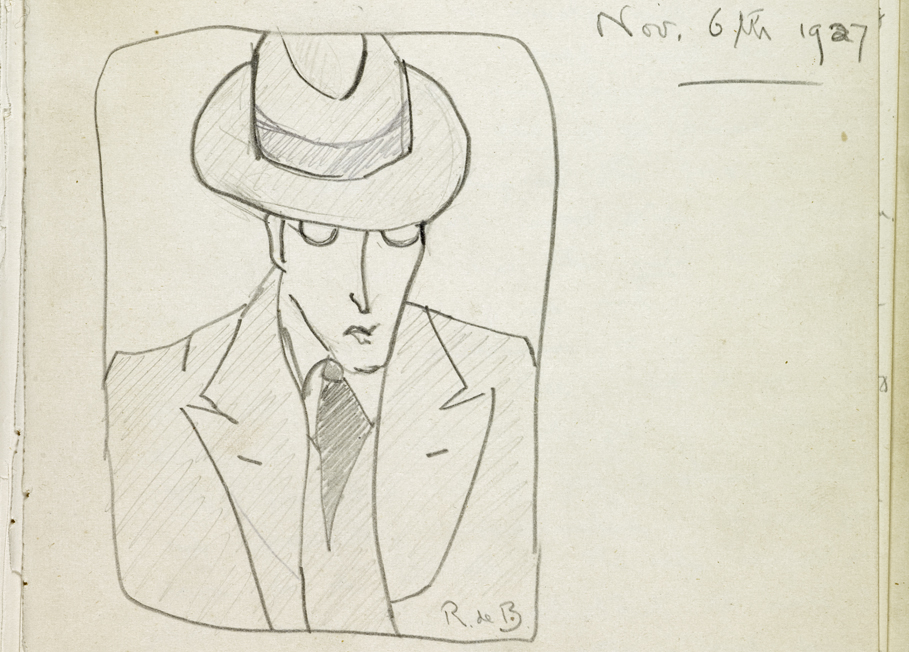

A page from an early diary.

Courage was a contemporary of Frank Sargeson and Charles Brasch, but he is much less known than them. This is a shame – he is an engaging and sometimes provocative writer. There are eight novels, several plays, numerous short stories and quite a few poems. But Courage, who grew up in Canterbury and lived most of his life in London, seems to be only half-remembered in New Zealand.

The embargo on his fourteen personal diaries expired in 2005, and I rushed into Dunedin’s Hocken Library to prise open the small leather notebooks and the loose-leaf pages tied up with ribbon. There is a pencil sketch in the second diary, with a long thin face and studious spectacles. This is how I pictured Courage as I read through the diaries that span the years between 1920, when he was a schoolboy of 16, and 1963, the year he died. He was a reserved and complex man. I learned about his personal relationships, especially his many male lovers; his experience of the Blitz, when he cowered with the neighbours in a cupboard under the stairs ("dreadful nights … made hideous with bombs and fires"); and the Freudian psychotherapy he undertook for depression near the end of his life.

Courage could be circumspect in his writing. He wrote discreetly about a heterosexual couple having sex in the bomb shelter in the basement of his apartment building. But he was much less reserved when he described his own interest in attractive young sailors and a range of other likely lads. Along with the jaunty young servicemen he picked up on the streets of London or the Cornish town of St Ives, where he often spent his summers, Courage had three notable relationships. The first was with Frank, whom he met on a train winding its way through Cornwall. The pair lived together in London for a while before Frank left for Argentina. Courage took a sea journey to visit Frank there, and they posed together for the camera. Courage stands shyly, skinny legs sticking out below baggy shorts. Chris, a handsome seaman, spent time in Courage’s flat in London. This was an austere white box: its décor consisted of a grand piano and a single framed painting – but Chris livened it up with his affable personality, and plenty of beer and sex. Courage was devastated when Chris was killed in action in the Mediterranean. Steve, Courage’s third mainstay, was a militant trade unionist who looked after the ailing author in his later years, picking him up from the hospital and helping with household chores. The diaries include explicit details of the couple’s intimate life, but they also make it clear that the men were not “married”, as Courage put it. Neither were they monogamous (Courage never had been at any point in his life), and they didn’t have to approve of one another’s friends.

James Courage (right) and his lover Frank Fleet in Buenos Aires.

Given his diffidence, I wasn’t surprised to discover that Courage often found social occasions tricky. Brasch described his friend as a witty and engaging guest at a party, interested in what was going on around him. But this isn’t how Courage imagined himself. He remembered quietly hanging back in the corner, nervously watching others – and later he headed home to write about their appearances, attitudes and characteristics in his diaries. I enjoyed his accounts of drinking beer with a “small but hilarious party of ghastly people”, and spending time with a “boring colonel with a charming Russian wife”. Courage must have been an enigmatic companion.

As accomplished as he was, Courage found writing hard work. Crafting a single sentence could take two hours, and the whole process often drove Courage into a state of nervous exhaustion. After he finally finished Desire Without Content, a grisly gothic tale about a woman whose husband drowns their baby in a fit of religious mania, he ended up in a Hertfordshire mental hospital, “hardly knowing what I was doing”.

But there can be no doubt about his literary triumphs. Private History, his 1938 play about sexual relationships between English schoolboys, attracted capacity audiences at London’s bohemian Gate Theatre Club – and rave reviews in the liberally-minded newspapers. As a queer pioneer, Courage wove subversive characters into the books he wrote for polite, middle-class audiences. Fires in the Distance, published in 1952, included Kathy, a masculine young woman, and Leo, a feminine young man. Leo moved from the Canterbury high country into Christchurch to work as a barman and find queer friends. A Way of Love, set in London, told of a domestic relationship between an architect, Bruce, and a younger man, Philip. It is polite, even by Courage’s standards – he described it as “timid … a mouse of a novel” – but many gay readers loved it. “It’s difficult to express appreciation of such a fine work, indeed almost impossible”, a display artist from Invercargill wrote. “I like everything about this book. It’s so human.”

I think of Courage as an early – if self-doubting – gay activist. He defended the rights of “inverts”, an early-twentieth-century term for men who desired their own gender, insisting that sex between men “has every scrap of right to be considered as normal as that between men and women”. At the same time, I got the sense he was never completely comfortable about either his sexuality or his politics. He often regarded homosexual men as unhappy or socially compromised. This isn’t surprising: public attitudes remained deeply ambivalent – and sometimes openly hostile – during his lifetime. Courage became a socialist during the 1940s, irritated by the English class system and blaming the war on competing capitalist systems. His views infuriated his National-voting parents and beloved grandmother back home in Canterbury – but he continued to ask for and receive cash payments from his father. The irony was not lost on him. “As a rentier I am a sinner”, he wrote in his diary, vowing to live more humbly and advance the good of others.

There hasn’t been a lot written on histories of New Zealanders with depression. Courage’s spidery writing covers 2000 sides of A4 which he referred to as his “Diary of a Neurotic”. He spent hours and hours on the couch during the 1950s and early 60s, an era before patients had ready access to anti-depressants. He poured out his heart to Edward Larkin, a rambunctious therapist from Australia. In line with Freudian thinking, Larkin encouraged Courage to blame his parents for his mental distress, and his mother was horrified at copping much of the blame for her son’s unhappiness. His often-harrowing account of his therapy holds back nothing in the way of sexual detail: he crafts explicit descriptions of his sexual acts and fantasies and what they might mean therapeutically.

As I read the diaries, I grew to like Courage a lot: parts of him remind me of myself, especially when it came to writing. He talked about moving words around on the page, “all very cold at first, but gradually warming up to creation-heat”. This is how I write too. Sometimes, though, his life seemed far away from mine – profoundly shaped by the experiences of war and a very difficult moral climate. He was fearlessly brave, and paved the way for people like me to write about gay things.

*This piece was first published on Newsroom, under the same title.