A Classical Memento

One afternoon I heard a synchronised thudding coming from the house over the road in the Dunedin suburb where I live. I knew it was due to be demolished and replaced with five townhouses, but what was going on? As it turned out, kids with hammers and axes were bashing and hacking inside. Through the windows I could see them hurling heavy tools at the plaster walls, leaving scars in what had been a rather handsome 1930s house. (I later learned they were the developer’s offspring.) The next day, when I ventured over for a look, I found a hatcheted mess. Plaster dust hung in the air and sneaked into my lungs. In the hall, lying sadly on the floor, were four battered plaster corbals that held up an archway until it was pulverised into pieces. Corbals are classical architectural elements like we might see on a Greek temple, or a Victorian fireplace surround. These ones are decorated with acanthus leaves which symbolise immortality and rebirth, a plant motif that also appears at the top of Greek Corinthian columns. I picked them up and carried them over to our place. I was sad that a fixable home was being destroyed, but relieved I’d managed to get a souvenir of a house that stood opposite ours for decades.

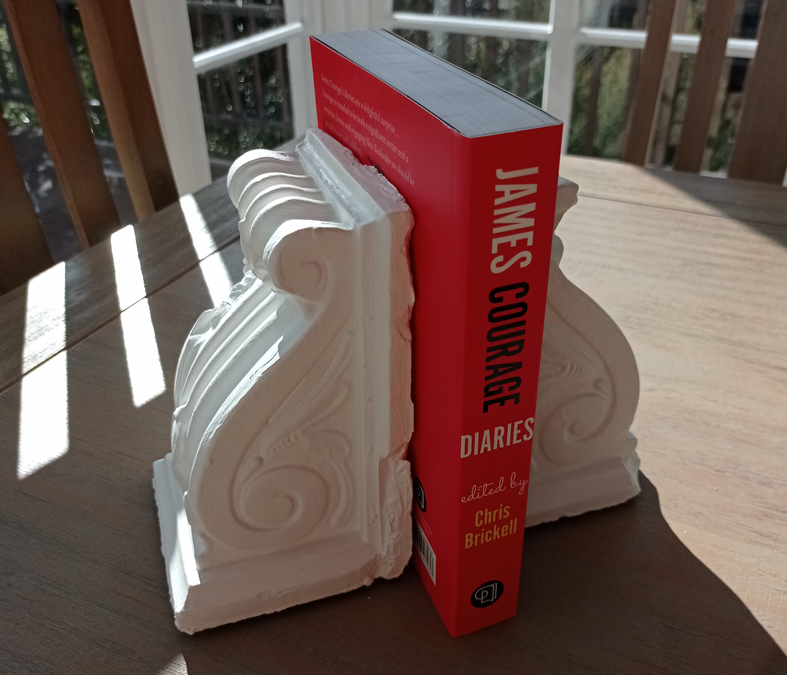

Above: Acanthus leaf detail.

I toyed with the idea of making the corbals into little shelves for trailing plastic plants, but I preferred my second idea: turning them into bookends. I had recently restored a little rimu bookcase – the writing on the back told me it had once been purloined from the Chemistry Department at Otago University – and it needed some bookends. As I looked at the chipped corbals, I thought of the Greek statues I had seen with no arms or missing noses. Were the Dunedin teenagers like the ancient tomb vandals who desecrated antiquities and left them with permanent scars? Hardly. My finds were prosaic fibrous plaster items, probably eased out of a mould in a Dunedin factory. And the house was going to be demolished anyway.

On the workbench in our basement, I carefully cut the loose fibres from the corbals while leaving the jagged edges where shards of plaster had chipped off. I painted them in Resene Alabaster, a white with tinges of green/brown/grey. This felt apt: alabaster is a type of rock that the ancient Greeks and Romans carved into vases and sculptures. Then, in a modern twist, I stuck on little plastic feet from Bunnings.

One of the reborn bookends sits next to a copy of James Courage Diaries. Courage was a Canterbury author born in 1903 who lived most of his life in England, and in 1959 he was the first New Zealander to publish a gay novel. For men of his generation, the classical world, with its armies of male lovers and various kinds of same-sex relationships, was an inspiration. So too were the nude male classical statues that posed, wrestled, and threw the discus. During a 1927 visit to Athens and the Parthenon, Courage ‘seemed to live most intensely … The light of the setting sun turned the marble to an indescribable, glowing pink’. He took home a flake of the marble from the floor of the Parthenon and stowed it among his own possessions.

As I prepped and painted my new bookends, I thought Courage might be pleased that an edition of his diaries sits alongside a latter-day piece of suburban classicism. When I look at the rescued plaster bookends I think about the long strands that draw together the ancient world, a pioneering New Zealand writer, and queer souvenir hunters like me.

Above: A Greek temple from James Courage's archive. This temple has Doric capitals on its columns, rather than the Corinthian capitals that draw their inspiration from acanthus leaves.

Above: A 1938 passport photo of James Courage.

Source

Chris Brickell (ed), James Courage Diaries, Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2021.